Category Archives: Uncategorized

Plastic = Endocrine Disruption: An Urgent Message from Jeff Bridges and the Plastic Pollution Coalition

Filed under endocrine disruptors, Uncategorized

DES: An Endocrine Disruptor With Tragic Effects on Mothers and Daughters

Similar to the thalidomide tragedy of the 1950’s, the story of DES exemplifies the suffering caused by a mix of profit-motivated medicine, lack of scientific evidence, and oversimplified assumptions about women and their bodies. First-year Lehigh student, Katie Bashus, weaves the history of DES with the history of ignoring women’s perspectives.

The person who discovered DES did so in the course of studying the carcinogenic effects of various steroid molecules, so it shouldn’t be a surprise that DES was later found to be carcinogenic, after having been prescribed to women for many years. DES stands for diethylstilbestrol. Its formula is C18H20O2, and it has a structure that allows it to mimic, at least in some ways, the action of the naturally-occurring steroid hormone, estradiol. DES has a long and sordid history, having been prescribed to women for over 30 years, and then later found to be carcinogenic (causes cancer), mutagenic (causes genetic mutations) and teratogenic (malforms embryos). DES has had devastating physical and mental impacts on mothers as well as on their children. These effects of DES include clear cell adenocarcinoma (a type of cancer most common in elderly women) in girls and young women. How did DES, at the time a suspected carcinogen, infiltrate the medical world and the world of thousands of mothers and their families?

Menopause as a Disease

Doctors of the mid 20th century, the vast majority of them male, noted that at the end of their reproductive years, females experience a decrease in circulating ovarian hormones, especially the class of ovarian steroids known as estrogens, which include estradiol and estrone. Many saw this drop in ovarian steroids as a disease or medical problem, and their records indicate that their main focus was the lack of “femininity” they saw in women over the age of 40. Based on the fall in ovarian steroids and subsequent loss of femininity they conjectured that the “treatment” for the “disease” of menopause would be to increase estrogen levels by some sort of pharmaceutical prescription. At the time, a cost-effective, painless way of providing real estradiol had not yet been invented, so some scientists looked for a cost-effective alternative to real estradiol.

DES As A “Cure” for Menopause

Sir Edward Charles Dodds thought he had found the estrogen alternative that the pharmaceutical industry was seeking. Dr. Dodd was a researcher studying carcinogens and the link “between estrone and a group of carcinogens known as the phenanthrene group.” In 1938 he discovered an estrogenic chemical, DES, that could be synthesized very cheaply from coal-tar derivatives. Dr. Dodd never patented his discovery, and since distributors didn’t have to pay any royalties, this made it an attractive alternative to replacement estrogen.

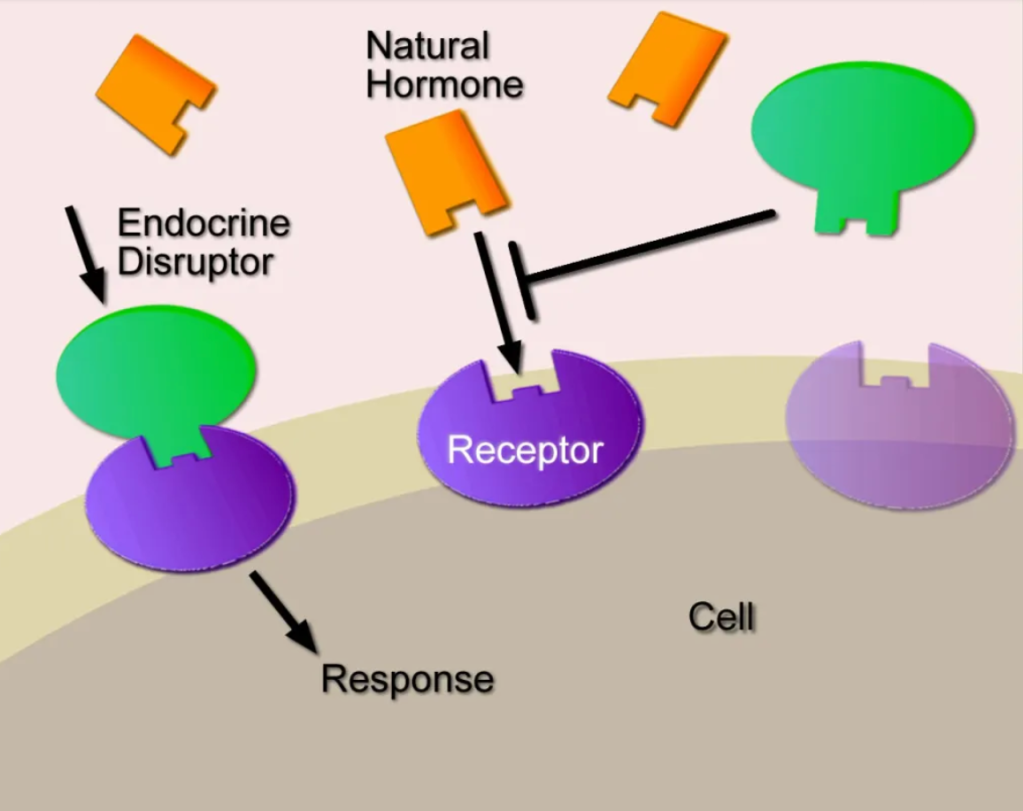

DES is a type of endocrine disruptor that blocks the action of hormones that already exist in the body. Normally, hormones control processes in the body, including “development, growth, reproduction, metabolism, immunity and behavior.” They are secreted in precise time patterns and amounts that allow organisms to synchronize their bodily systems with the day-night cycle, meals, times of year, and phases of their life history. Endocrine disruptors interfere with these processes. Nuclear receptors are the main target of both endocrine disruptors and natural hormones. Normal steroid hormone-receptor complexes form, travel into the nucleus, and interact with DNA, acting as transcription factors. Endocrine disruptors typically come from outside the organism, and many either mimic or block the action of steroid hormones. Rather than rewriting the DNA sequence, endocrine disruptors such as DES have epigenetic effects that alter the timing of DNA expression. Such effects can be as serious as a genetic mutation and be passed to future generations. Even after exposure is over, endocrine disruptors’ health effects linger, having set in motion developmental chain reactions that cannot be undone.

Ignoring the Animal Studies

As explained in the book Toxic Bodies written by Nancy Langston, there were early indications that DES could have significant effects on mothers and their offspring. In one study, researchers gave DES to pregnant rats, mice, and chickens. The offspring exposed to DES were found to have changes in traditional sexual differentiation (females were masculinized), but problems were only seen when the treated animals reached sexual maturity. Another study found this similar exposure made the adult offspring of DES-exposed mice act more aggressively. Dr. Dodd’s research group found DES led to atrophy in reproductive organs. Some research scientists saw the red flags, but only those who understood that the reproductive systems of laboratory rodents share many important similarities with those of primates. Humans are a species of primate.

Then how was DES distributed to thousands of women even though animal studies indicated numerous problems? Some doctors thought DES would be safe because women already have estrogen in their bodies, so the post menopausal woman should be fine. Contrary to this belief, many biologists believed that the results of experiments on mice provided cautionary evidence. Physicians discredited this idea. They claimed that humans are different from animals, and women would not develop cancer from having extra estrogen. Their point of view was bolstered by the fact that cancer can take years to manifest. In other words, a lack of evidence of damage was seen as evidence of safety. Did all or even a majority of women want to “cure” menopause? Another point to consider is that most physicians at the time were men, and one wonders whether they valued or even solicited the opinions of females. Remember that at this time, the physicians expressed concerns about the femininity of older women, not their health.

The FDA Under Pressure from Industry

Initially, the FDA rejected DES to be used medicinally for menopausal women because of the carcinogenic and toxic effects. Their spinal cords crumbled, however, after pushback from the pharmaceutical industry and a court case. The FDA was brand new and members didn’t want to be seen as an enemy to drug companies for fear of losing their standing. The FDA therefore approved DES to cure menopause as long as information was provided on the possible adverse side effects and if it was only available by prescription. DES became the first medication deemed dangerous enough to warrant a prescription and became the first prescription drug in the US in 1941. Unfortunately, the information about DES’ toxicity was not given to physicians. The information was not even on the bottle; doctors had to write to the manufacturer to obtain that information. Most physicians did not seek to acquire the extra information. Their patients trusted DES because they trusted doctors. So a combination of mistrust of animal testing, no signs of immediate harmful effects in humans, a misogynistic mindset, and an inexperienced FDA led to the approval of DES to treat menopause.

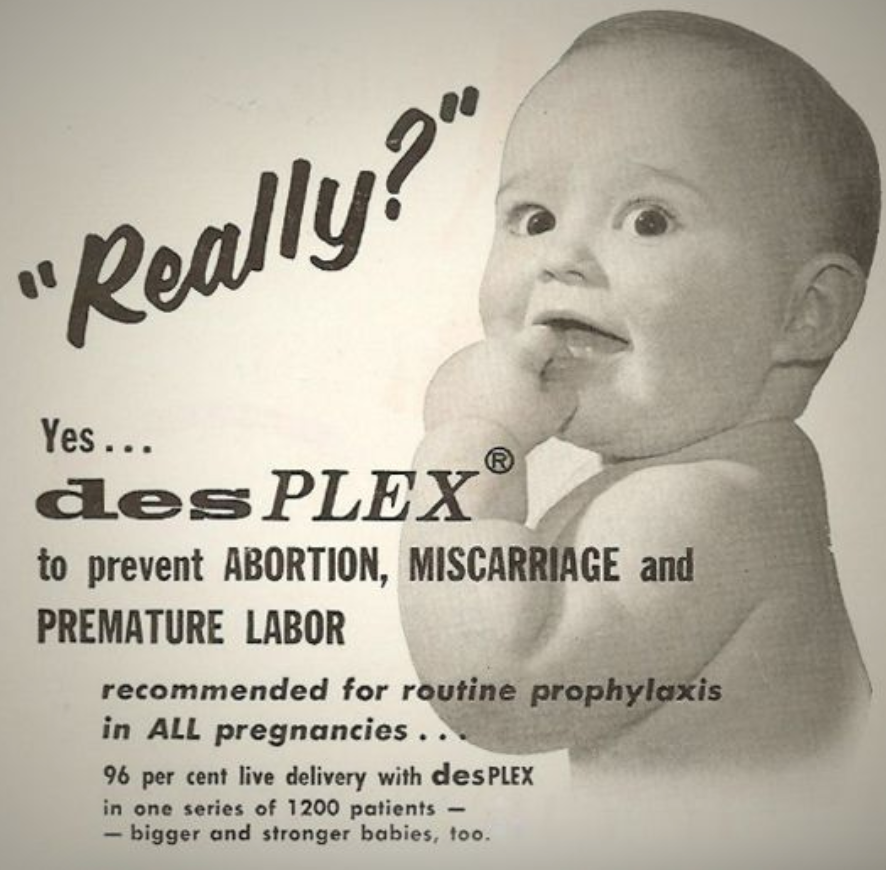

DES To Prevent Miscarriage (not)

The use of DES as a treatment for menopause was short-lived, and an alternative market was quickly sought and discovered. After a while, a newer medication with fewer side effects called Premarin (isolated from the urine of pregnant horses) became the primary choice for menopausal women, so the pharmaceutical companies manufacturing DES had to switch gears and find a new market. Two Harvard researchers postulated that DES could help pregnant women. They reasoned that, since elevated estrogen levels during pregnancy usually stimulate the hormone progesterone, which the uterus needs to sustain pregnancy, increasing estrogen action by giving DES would prevent miscarriage. Their evidence was so thin as to be nonexistant, and we know now that their decision was dead wrong. One “study” examined diabetic women because they were considered to be at a high risk for miscarriage. The study consisted of six pregnant diabetic women, all given DES. That’s it. First of all, this sample size is ridiculously low. Second, there was no control group of diabetic women given placebo and no group of nondiabetic women to ascertain the rate of miscarriage. Of the six babies from diabetic mothers treated with DES, five carried their babies to term. From this they concluded that DES successfully prevented miscarriages. Nevertheless, DES found its place as a drug for diabetic women claiming to ensure healthy pregnancy without miscarriage, and gained approval in 1947. This distribution limitation (to diabetics) on the medication was not enforced as time went on, so eventually, many non-diabetic women were taking it during pregnancies as a supplement. In fact, DES was prescribed willy nilly for a number of loosely related uses. It was prescribed to prevent premature births and miscarriages, treat infertility of gynecological disorders, and inhibit milk flow after childbirth. The philosophy seemed to be “why not?” The belief at this time was that the placental barrier between baby and mother was impermeable so that nothing could get through from mother to child. This was later refuted and was a part of the reason that babies and not just the mothers were affected by DES. The expansion of DES usage was allowed by invalid assumptions, poor experimental methods, and disregard for the limitations on its prescription.

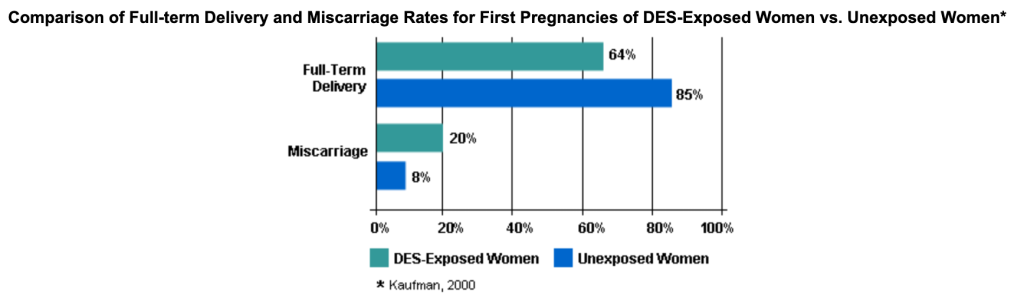

Scientific studies performed years after DES became a common pregnancy supplement showed that it was not beneficial to women. It did not prevent miscarriages and could do great harm to the daughters of DES mothers. In 1953, a study showed DES was ineffective at sustaining a pregnancy – 840 pregnant women on DES, 804 in the control group, and no discernible difference in the pregnancy outcome.

Despite this, DES continued to be prescribed for decades. The first red flag that DES was harmful was when an extremely rare cancer of the cervix was found in DES daughters in 1971. It occurred in their teens or early 20s, while this cancer typically happens much later in life. Clear cell adenocarcinoma, CCAC, was present in 1 in 1000 DES daughters. Shortly after that study, DES usage was stopped in the United States, but DES usage in Europe did not stop until around 1979. The increased risk of cancer from DES, though, was just the tip of the iceberg.

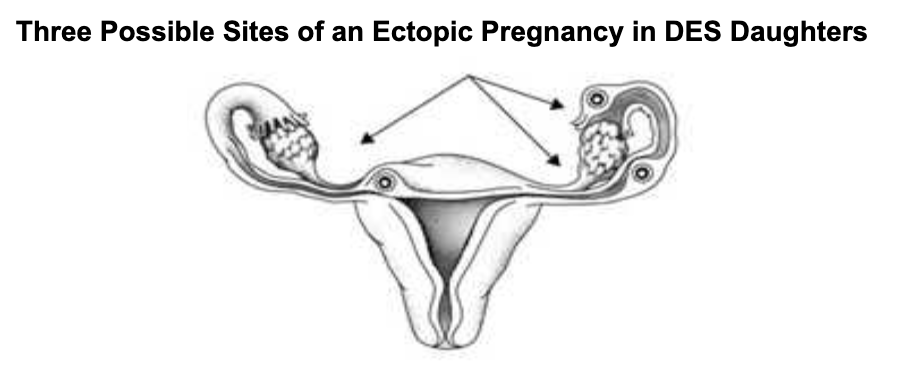

Other physical issues caused by DES were found in many later studies. The mothers who used DES had a 40% increase in the likelihood of getting breast cancer later in life. The primary victims of the DES exposure, however, were the children, both male and female. Cell alterations, cancer, and cysts were on the list of effects on the children of DES mothers, and there was also harm to fertility. Male genital anomalies were 200% higher than the general population. Some 95% of DES daughters had one or more reproductive issues. There were increased risks for infertility, miscarriages, ectopic pregnancies, and premature births. Infertility went up 30%, miscarriages went up 90%, and premature births increased 180%.

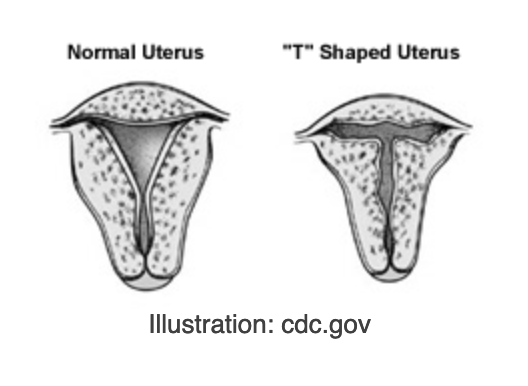

The reproductive issues in the offspring were often traced to malformation of the Müllerian ducts. With the right hormonal environment, Müllerian ducts in the fetus develop into fallopian tubes in females and completely disappear in males. These studies often saw that the fallopian tubes were not properly developed, and some Müllerian duct remained in men, which caused feminization. The abnormally T-shaped uterus became diagnostic for DES exposure. The presence of DES during development seemed to have affected the tubes’ proper development.

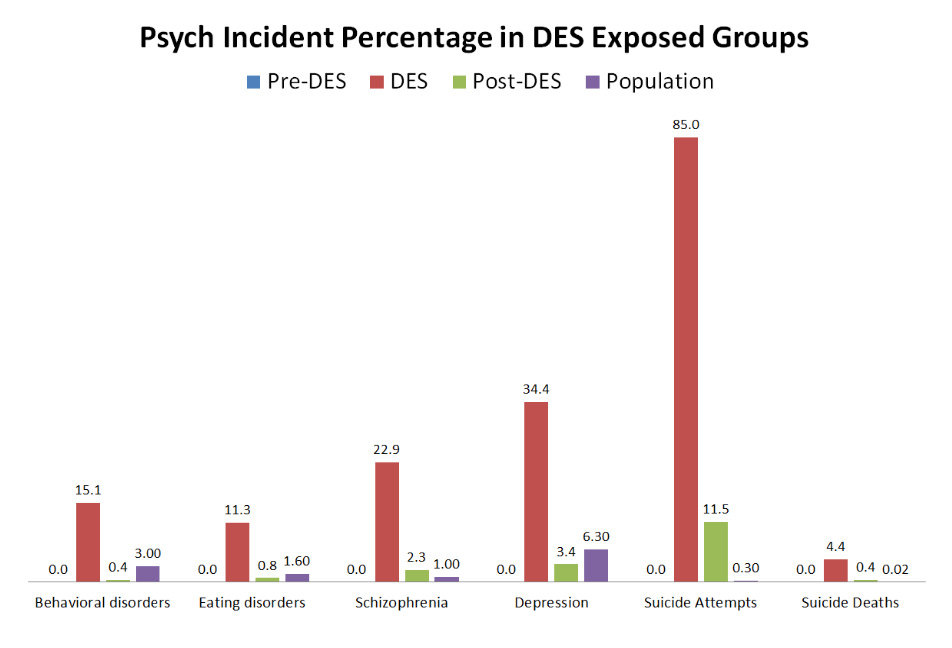

The effects of DES on offspring were not limited to the physical; a higher incidence of psychiatric disorders has also been discovered. A study conducted in France sent a questionnaire to women who took DES and had children between 1946 and 1995. Some 1182 children were reported on, including DES exposure, medical history, and occurrence of any psychiatric issues. The children were separated into three groups: children born before their mother took DES, children exposed to DES while in the womb, and children born after the mother stopped taking DES. The data shows a considerable increase in mental health diagnoses after DES was introduced into the mother’s system versus that of the general population. A surprising result is that children born post-DES showed a higher likelihood of mental illness than the general population. This suggests that DES was stored in the mother’s body after she stopped taking it and was later released. The increased occurrence of psychiatric disorders in the DES-exposed children, summarized in the chart below, shows the dangers to the brain and its development.

Soyer-Gobillard, Marie-Odile, et al. “Association between Fetal DES-Exposure and Psychiatric Disorders in Adolescence/Adulthood: Evidence from a French Cohort of 1002 Prenatally Exposed Children.” Gynecological Endocrinology, vol. 32, no. 1, 2015, pp. 25–29.

Why might these issues be occurring in DES offspring? Well, some evidence supports the idea that because the HOX genes are involved in the structural differentiation of the reproductive anatomy, DES delays the expression of these genes, causing the misprogramming of the molecules themselves, which can result in different anatomies or tumors. Also, demethylation, removal of CH3 from a molecule, “of the estrogen-responsive gene LF in the mouse uterus” was shown and could be another reason for issues with sexual differentiation in offspring. The ADAM TS9 gene is involved in controlling the development of the shape of reproductive organs and the development of the central nervous system. DES has been shown to alter the expression of the ZFP 57 gene on chromosome 6, affecting neurodevelopment and neuroplasticity. These epigenetic effects are just as scary as direct DNA altering, that is, genetic mutations.

DES use has been well investigated, and all evidence shows that DES is a dangerous endocrine disruptor. After being prescribed for menopausal women and then pregnant women, it was shown to be a threat to the physical and mental health of not only said women but also their offspring. Even after clear evidence of zero protection against miscarriage and harmful effects on mothers and offspring, DES was prescribed for decades. It is no coincidence that any and all benefits were accrued by the pharmaceutical industry. The continued sale of DES was aided by doctors’ failure to keep up with and heed the data supplied by the scientific experiments. Knowledge of this history is important because it reminds us that flawed decisions result from sexism and putting profits ahead of the health of women. Thousands of women were unknowingly taking toxic chemicals that would affect their children. The history of the approval of DES demonstrates the dangers of misguided assumptions, inadequate testing, and an FDA too willing to ignore the science to please the pharmaceutical industry. I think that the evidence in these articles is powerful and provides adequate proof of the dangers of DES. This research could still go on into the future because the full, long-term effects are not yet known in humans. Studies on DES grandchildren are still in progress, and we don’t yet know how far in the future DES will affect subsequent generations.

Filed under endocrine disruptors, rock, Uncategorized

The Joke’s on You: Gender Bias in How Humor is Perceived

Wow! Fantastic post by Dr. Nancy Wayne on a recent study documenting how humor enhances the status of funny men while diminishing the status of humorous women. I’ve always been vaguely bewildered about how my jokes are perceived, but it’s absolutely mind blowing to see the data!

I think of myself as having a good sense of humor. I like to laugh, and I often use humor as a way of connecting with people during work and play. I use humor and storytelling a lot when teaching—I thought it was an effective way of engaging students and enhancing their ability to understand and remember complex physiological concepts. And with some exceptions, student evaluations supported that notion. I use humor a lot when interacting with my colleagues as a way of connecting with them and diffusing tensions during difficult conversations—I thought it was an effective way of communicating, until I received a “360 feedback evaluation” in which about half the evaluators said otherwise (see Bringing Your Authentic Self to Work).

There has been a lot written about the power of using humor during business transactions and in the classroom, including research studies supporting the use of positive…

View original post 958 more words

Filed under Uncategorized

A-well, a bird, bird, bird, bird is a word

Rebecca Calisi produced a must-see video (below) explaining the importance of bird research for understanding the brain. Please share it widely, because despite the obvious importance of bird research, there are still many who don’t get it, and misunderstandings and assumptions about bird researchers are rampant. As you will see, the video is geared toward those who are completely in the dark about bird research and those who conduct bird research.

Rebecca Calisi produced a must-see video (below) explaining the importance of bird research for understanding the brain. Please share it widely, because despite the obvious importance of bird research, there are still many who don’t get it, and misunderstandings and assumptions about bird researchers are rampant. As you will see, the video is geared toward those who are completely in the dark about bird research and those who conduct bird research.

We share so much in common with birds (ahem, evolution), and so our understanding of the brain, and especially hormone-brain interactions, has been shaped by bird biologists. Here are just a few examples…

- The first evidence for hormone effects on brain and behavior were performed by Berthold in the 1800s; he studied roosters. He didn’t call the secretions hormones, but his work marks the beginning of endocrinology (the study of hormones, like those that control puberty, sexual desire, and the hormones in oral contraceptives and cancer treatments) and neuroendocrinology (the study of how hormones affect the brain and nerves in the body).

- In the 1920’s Rowan discovered that day length (number of hours of light in a day) stimulates the reproductive hormones and behavior in dark-eyed juncos. This work initiated the field of seasonal biology and the effects of light and dark on mood, learning, depression, reproduction, and adaptation to seasons.

- In the 1960’s Hinde and Lehrman opened an entire field of research based on their evidence that hormone-behavior relations are reciprocal, that is, hormones affect behavior, but changes in behavior affect hormone secretion. This research was on ring doves and canaries, and lead to the study of how our behavior and cues from our peers influences our own internal secretions (such as testosterone, serotonin, and dopamine).

- Nottebohm and Konishi and their academic offspring made pivotal contributions to understanding how changes in brain cells (neurons) allow birds to learn songs of their own species, songs that they use to hold territories and compete for mating partners. This work with song birds is key to understanding how the brain learns and changes with experience including experiences with our sexual partners, experiences with stress and trauma (PTSD), and experiences with nurturing kindness from our caregivers.

- Schlinger and Brenowitz discovered that rapid changes in the brain and behavior involved the enzyme, aromatase, in specific parts of the brain. This work with zebra finches and other species, is important for understanding the underlying cellular mechanisms involved when hormones have rapid effects on behavior, and when the behaviors of one individual affect the behaviors of another. It’s also important for understanding how brain cells survive trauma.

Again, these are just a few examples of why bird is the word.

Filed under Oldies, rock, Uncategorized

I Would Die 4 U (and my genetic contribution to future generations)

We knew that praying mantis females often cannibalize their mates after sex, and we suspected that there was some benefit to the male that would outweigh the cost, but why not just take the female out for an expensive dinner? Now we have some evidence. These clever experiments show that cannibalized males make a greater somatic investment in their offspring leading to higher fecundity in the female. Check out their hot experimental methods for determining male investment in offspring bodies.

This post is dedicated to our beloved formerly alive One

Filed under Funk, Uncategorized

He’s A Rebel! Paul Heideman visits Lehigh

This week the Schneider lab had the pleasure of hosting one of our scien ce heroes, Paul Heideman from The College of William and Mary. He doesn’t wear a leather jacket or anything, and in fact, he looks like a typical white-guy professor. We’re still wondering exactly how he left us so inspired and energized, like we just discovered the thrill of science all over again.

ce heroes, Paul Heideman from The College of William and Mary. He doesn’t wear a leather jacket or anything, and in fact, he looks like a typical white-guy professor. We’re still wondering exactly how he left us so inspired and energized, like we just discovered the thrill of science all over again.

Like most of us, Paul came up the ranks when everyone was advised to learn super cool state-of-the-art molecular techniques, to work on conditional knock-out/knock-in-optogenetic-whatever-the-hell mice, and to focus on cellular mechanism. Did he do this? No. Is he tenured? Yes. Is he funded? Yes, well funded. Is he happy? He seems pretty darn ecstatic.

Second, he studies the one thing that most biologists avoid like the plague: Individual differences. Most scientists seek to minimize them. They like groups that show little natural variance, and they omit outliers.

Hating individual differences makes sense in a way. When a drug works to reduce pain or fight infection, you want it to do so reliably in just about everyone. Will a new drug X decrease depression? We want a clean result. We want to see clear differences in depression between the drug-treated and placebo-treated groups. We want as little variation as possible within the groups. Face it. Too much variation within the treated group, and the drug is not going to market.

Vive la diffe’rence!

Paul solved the problem of individual differences by embracing them. He started his career in the field, trying to figure out why some equatorial animals are seasonal breeders and some aren’t. Fruit bats (a.k.a., flying foxes) that inhabit particular islands in the Philippines breed only in certain seasons, whereas those on other islands begin their breeding season months later. Presumably, this ensures that offspring are born at the time when they are most likely to survive. But what is the source of the difference?

Paul solved the problem of individual differences by embracing them. He started his career in the field, trying to figure out why some equatorial animals are seasonal breeders and some aren’t. Fruit bats (a.k.a., flying foxes) that inhabit particular islands in the Philippines breed only in certain seasons, whereas those on other islands begin their breeding season months later. Presumably, this ensures that offspring are born at the time when they are most likely to survive. But what is the source of the difference?

To be a seasonal breeder, you need an internal clock, a reliable cue in the environment to set your clock (like the availability of food or the day length), and a sensory system to detect the environmental cue. Also, you need your clock and your senses to be connected to your reproductive system, and ultimately, to your gonads (ovaries or testes). What’s up with a nonseasonal breeder? Is the clock broken or are they deaf to the alarm? Is there a disconnect between the clock and the gonad?

Now What?

Paul was stuck. He just couldn’t figure this out in the field. In order to uncover the internal brain mechanisms, he needed to have animals in the lab. Commercially available lab animals, however, will not do. They gots no variance in the thing he wanted to study. Most lab animals are uniformly year-round breeders. He would have to create a lab population that had the same variation that exists in nature.

Paul was stuck. He just couldn’t figure this out in the field. In order to uncover the internal brain mechanisms, he needed to have animals in the lab. Commercially available lab animals, however, will not do. They gots no variance in the thing he wanted to study. Most lab animals are uniformly year-round breeders. He would have to create a lab population that had the same variation that exists in nature.

Being a rebel, he did what all of his colleagues were not doing. He trapped wild mice (Peromyscus leucopus) from the wild, brought them to his laboratory, and began crossbreeding. He kept the population large enough to avoid inbreeding (breeding close relatives tends to decrease heritable variation). Now he had a lab population that contained most of the variation that existed in the wild. How would he make use of this to answer his questions about individual differences in seasonality?

The next thing he did was brilliant. This base population served as the starting point for a selective breeding program. He started breeding lines of mice that differed in their seasonality. By breeding seasonal males to seasonal females, and unseasonal males to unseasonal females for many generations, he ended up with two groups of animals that differed from each other. They didn’t just differ by accidental inbreeding, or for other unknown reasons. They differed because they were selectively bred for those traits he wanted to study.

Paul has created and maintained a scientific gold mine. He can expose the two groups to winter conditions, measure their hormones and neuropeptide levels, and figure out what accounts for their differential response to the changing season. He can even sequence their genome and look for differences. He can get answers to questions like “How does evolution change the reproductive system?” “Can natural selection change hormone levels or does it change hormone receptors?” “In nonseasonal animals, is their internal clock broken or are they simply blind to the seasons?”

To find out the answers, you can check out Paul’s work here and here. Paul writes, “I have worked on multiple populations, but my current mice all come from one population. That’s important to me because I can say that all this variation is just from one little population — and that suggests that other mammals, including humans, might also contain large amounts of variation.”

I agree and I think it’s especially cool that selection has created wildly different strategies for survival and reproduction within the same species. In this case, you’ve got cautious mice that take the hint that winter is on the way by shutting down the reproductive system in order to conserve energy for survival in the cold. In the same population, you’ve also got flexible mice that will breed willy nilly as long as they can. If the winter is mild, the sexy mice beat the conservatives by producing litters and getting more genes into the next generation. If winter is harsh, the conservatives will win the gamble because they will be the only ones to survive to breed in spring. It takes all kinds. Vive la diffe’rence!

Paul gives a great talk. He gives all of his attention to the students, and he has tons of helpful advice about teaching behavioral endocrinology and science writing. Plus. . .

Filed under Oldies, Uncategorized

Happy Fat Tuesday from Schneider Lab

Hamster food hoarding (mean and s.e.m.) over the four days of the ovulatory cycle in food-restricted (open triangles, dotted lines) and food-unlimited (solid circles and lines) females housed with the choice between staying home, visiting a male, or hoarding food. The predominant sex behavior of the food-restricted female is shown in a cartoon above the hoarding data. On day 4 of the cycle, the periovulatory day, the females show mating behavior. On day 3, they show vaginal scent marking but do not mate. On days 1 and 2 they spend more time hoarding food than visiting the male. (Adapted from Klingerman et al., 2010 by Jay Alexander)

Brain cells stained for GnIH (red) and Fos (green). The red stain represents GnIH which occurs in the cytoplasm and thus colors a wide area of the cell body. The greed stain represents the proto-oncogene product Fos, a protein that is synthesized upon cellular activation. Fos resides within the cell nucleus. Cells that are red with a green/yellow stained nucleus are double-labeled with GnIH and Fos. These represent GnIH-containing cells that have been activated by food restriction. (Photograph and immunohistochemistry by Noah Benton)

March 1, 2014 · 4:40 pm